Last Friday (2nd April) I gave a presentation for the Cambridge Festival’s SciArt Soiree, speaking about data manifestation through Proboscis’ Lifestreams projects and the work I am currently co-leading on with the Manifest Data Lab at Central Saint Martins UAL: Little Earths with Dr Erin Dickson. It was an adaptation of a presentation Erin and I previously gave at the NERC Antarctic Science Conference, and which built on another she had given to the BAS Polar Ice-Core Forum (both in March).

The other speakers at the Soiree included Anna Phoebe and Natalie Stroeymeyt, with a performance by Ricky Chagger and Caroline Bouvier and it was organised and hosted by Sophie Weeks and Jacob Butler with help from members of the Cambridge SciArt Network.

In January 2012 Proboscis was invited to collaborate with Philips Research lab in Cambridge Science Park as part of the Visualise Public Art programme at Anglia Ruskin University. We had been developing the concept of “tangible souvenirs” for a number of years – essentially physical artefacts that were generated from ephemeral digital experiences that could act as mementos.

Our collaborators at Philips asked us (myself & my colleague Stefan Kueppers) to think about how we might create meaningful relationships to then new kinds of personal activity monitors (e.g. fitbits, smart watches etc). How might people change their behaviours if they could perceive unhealthy patterns develop over time? Already, industry analysis indicated that 90% of such devices were being abandoned by their users after 4 weeks. Philips were interested in what difference such devices could make to healthy lifestyles if people used them over decades, not just a few weeks or months.

As artists, our insight was to explore how humans invest meaning into arbitrary objects and use them both as triggers of memories and feelings. What if, we wondered, meaningful objects could be generated from biosensor data?

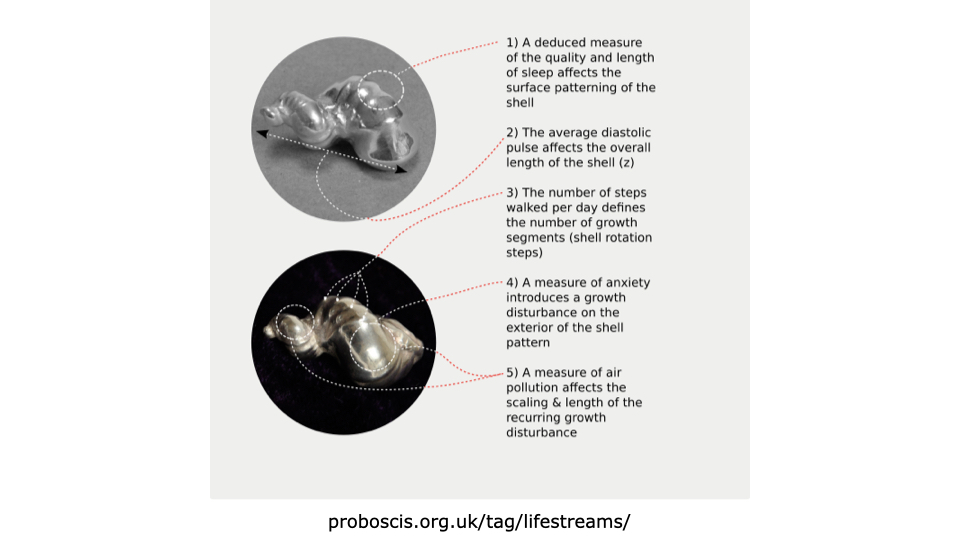

Above you see a Lifecharm Shell from our Lifestreams project, grown algorithmically from a set of 5 different data types which affect the growth patterning in multiple ways.

In 2016 we presented a new series of lifecharms at the Alan Turing Institute. These manifested data from a research project led by Professor George Roussos at Birkbeck University of London.

These shells are generated from a small subset of data from 4 individuals who all score similarly on the Unified Parkinsons Disease Rating Scale. This scale reduces 70 different motor function tests on how the disease is experienced by an individual, into a 1-100 numerical scale. But this means that people with vastly different experiences of Parkinsons can score similarly, and has implications for what care and therapy they might be offered.

Here you can see and would be able to feel that these four individuals experience Parkinsons in tangibly different ways, despite scoring similarly on the scale. The data manifestation here offers a tactile method to communicate a quality of experience to non-experts that a dashboard or a graph would simply not achieve.

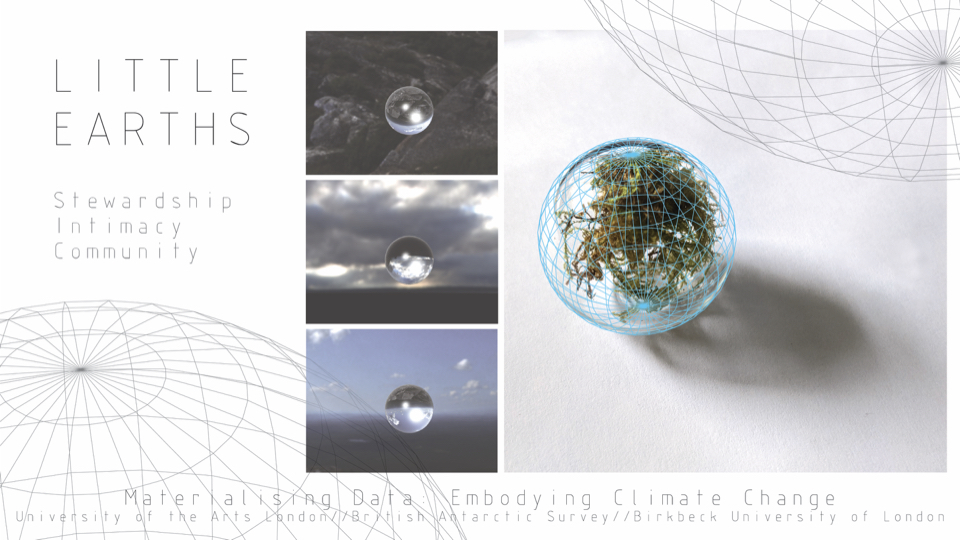

Our current project, Materialising Data Embodying Climate Change is a 3 year AHRC-funded transdisciplinary & collaborative project between Central Saint Martins UAL; Birkbeck University of London; the British Antarctic Survey in Cambridge and Proboscis.

The Principal Investigator is Professor Tom Corby, I am co-lead and the co-investigators are Professor George Roussos of Birkbeck, and Dr Louise Sime of BAS. The team includes Dr Erin Dickson, Gavin Baily, Dr Rachel Jacobs and Dr Jonathan Mackenzie; and our collaborators also include Cosmin Stamate and Dr Aideen Foley, both at Birkbeck.

I am going to focus today on Little Earths – a sub-project led by myself and Erin Dickson, our team specialist in digital fabrication and craft skills who created the following slides for presentations to the Polar Ice-Core Forum and the NERC Antarctic Science Conference last week.

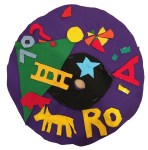

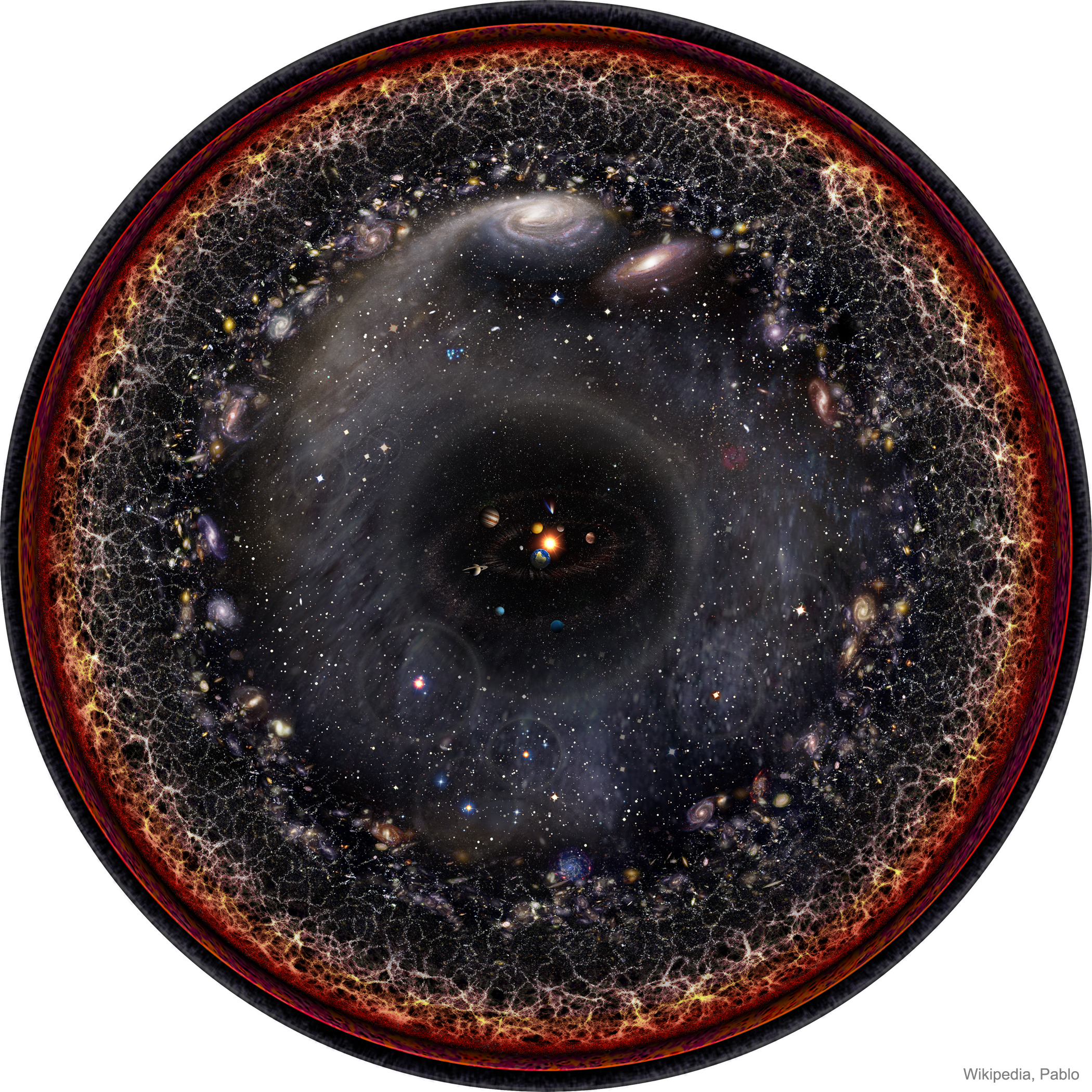

Little Earths are physical artefacts derived from climate data, digitally modelled and locally crafted, which represent the power and fragility of Nature’s environmental systems and our human relationships to it. They are actual manifestations not simply visualisations, activating new ways to appreciate data through embodiment can add to their scientific and cultural understandings.

These personal talismans invert the normal scale relationship between humans and the planet, and seek to engage members of the public in a durational artwork that pervades their everyday lives as an act of mindful care and reflection.

Focused around the themes of Stewardship, Intimacy and Community, Little Earths will be an emotional and sensory short-cut to knowledge through playful, social and imaginative connection.

Climate Change is an emtoive and often overwhelming subject. There are veritable oceans of climate data – but how are non-experts to make sense of them? Traditional visualisations of data such as graphs and dashboards often remain beyond the grasp of all but experts grounded in how to interpret them.

As artists, we can create methods that utilise the whole human sensorium for sense-making and interpretation, by making complex information tangible and appreciable in richer and more nuanced ways. Our approach departs fundamentally from normative data representations on computer screens. It embodies information in reciprocally interactive engagements that afford people greater use of their highly developed senses.

Thus “data manifestation” is intended to elicit “empathic encounters” with challenging or unfamiliar information and concepts.

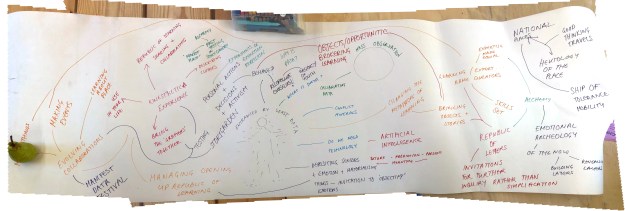

We are also working with three themes: touch, connect and immerse. And taking existing objects that have intrinsic understandings, and embedding additional meaning within them as an entry point to creating intimacy with participants.

We thought about objects that are already part of our lives and in our homes, objects which require stewardship or have become part of our daily rituals. The theme ‘touch’ lead us to objects which we hold or wear on the body. Keep-sakes and sentimental objects such as photos of loved ones, jewellery and quotidian talismans such as shells or pressed flowers.

Artefacts such as prayer cords, rosaries, worry beads or charm bracelets have been used for centuries, and are often adapted to the wearer, are. Already embedded with religious, spiritual or sentimental value, these objects also require a form of meditation from the user, with rituals including counting beads, repeating mantras or merely admiration of a growing collection.

Materials commonly used include shells, precious metals, stone, sandalwood, seeds, pearl and human bone.

The theme ‘connect’ is also at intimate scale, however instead of thinking about the body, we thought about the home.

Our worlds are becoming more and more digital, TVs, computers, mobile phones and even watches demand our attention rather than attracting it. Instead of instilling meditation and focus these objects instead invite addiction and distraction.

But objects still exist that are solely dedicated to the art of focus. Gongshi or Suseok, also known as spirit stones, are naturally occurring rocks which have been eroded by nature. The more complex the erosion, the more valuable the stone. Displayed on intricately carved wooden stands and placed on desks or in gardens, Gongshi invite the viewer to appreciate the power of nature.

But how can these natural objects be informed by or generated from data?

Using digital tools, such as 3D scanning, AI analysis and 3D printing, as well as material processes, such as throwing clay and glass blowing, it is possible to create contemporary interpretations of the traditional Gongshi, informed by data, resulting in a bespoke group of objects befitting of our contemporary lives.

Exploring natural erosion, as a craft specialist Erin was immediately drawn to experiments in clay. Here an thrown, unfired pot is submerged in water.

We can control erosion through variables such as time of submersion, water temperature and salinity, type of clay and form.

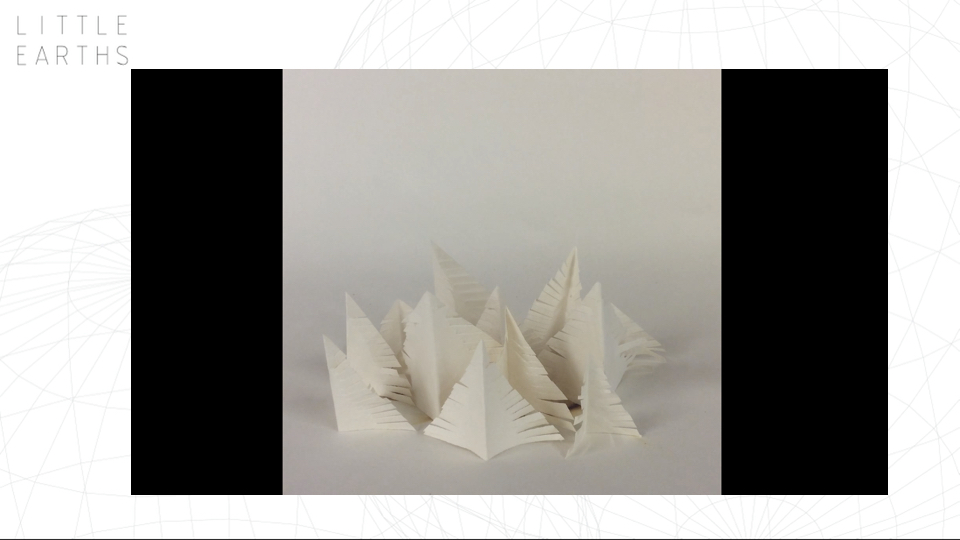

Here we see another of Erin’s experiments. Working in a glass hotshop, she experimented with the thermal properties of blown glass.

A glass bell-jar appears in the frame. Fresh from the furnace, the glass remains at up to 1200 degrees. The heat of the blown glass does not translate visually, but the effect is seen in the activation of its contents, and the residues they leave.

The relationship of the bell-jar to the paper forest is a microcosmic representation of the larger subject of climate change. Variables are more unruly here and is it difficult to control the temperature of the glass. What we can control are the forms within the dome, and the materials from which they are made.

For more information please visit our websites or get in touch.

You must be logged in to post a comment.